L&S

Learning

Support

Services

presents

TEACHING with TECHNOLOGY

ONLINE WORKSHOP SERIES | 2012-2013

Why Use Active Learning in Smaller Classes?

Observe & Consider

Observe & Consider

Lots of motion, little development, no progress. Not what we want in a learning environment.

Teaching in smaller classes offers all kinds of advantages: instructors can usually learn each student's name, tailor their instruction to class interests and ability levels, manage collaborative and cooperative projects, and more easily have meaningful interactions, including discussions, with the whole class. While smaller class sizes seem in some ways to lend themselves naturally to more effective active learning, there's no guarantee that a class will be actively engaged in learning simply because there are fewer students. Similarly, we should be careful not to confuse activity with learning; it is not the case that just because students are actively doing things that they are experiencing meaningful learning, in fact, some kinds of activity may actually detract from learning goals and prove detrimental in the long term. With that caveat in place, we believe that there are active learning is generally both a welcome and effective addition to most small to medium sized courses.

As a general rule, we'd suggest that active learning activities are most effective when they:

- Promote learners' thoughtful engagement with course material and the learning process

- Are accompanied by clear instructions and timely feedback (including any necessary correction)

- Are intentionally aligned with specific learning outcomes.

On this page we'll highlight some of the evidence for the impact of active learning practices on lerarning in smaller classes, focusing on two low-risk, high-impact elements: involvement and student cooperation and collaboration.

Why Involvement Matters

The highly influential educational researcher Alexander "Sandy" Astin (now emeritus at UCLA) spent much of his research career trying to understand which variables are most likely to predict student success in college. Through the course of his research, he became convinced that what he called "student involvement" was central to undergraduate success. In a now famous article, first published in 1984, Astin defined involvement as "the amount of physical and psychological energy that the student devotes to the academic experience," and argued that the amount of student learning and personal development that learners experience in an academic setting is directly correlated to the quality and quantity of the learner's involvement. Astin believed that the consequences of his findings were fairly clear: in order for a particular curriculum to succeed, above all else it must "elicit sufficient student effort and investment of energy," which meant that educators should "focus less on what they do and more on what the student does: how motivated the student is and how much time and energy the student devotes to the learning process."

How Involvement Affects Learning

In the subsequent decades, Astin's ideas have been deeply influenced several important developments in higher education, especially the development of what are often called learning communities (whether they be specialized dorms, first-year interest groups, mentoring relationships, service learning courses, language houses, honor societies, or even student orgs). Several thorough research studies have also confirmed many of Astin's core findings: for example, one study of over 6,000 students in introductory physics courses at two nearby state schools whose sports teams also wear red and white and will remain unnamed found that students' scored nearly twice as high on tests measuring their conceptual understanding in courses that used active learning methods than their peers in traditional courses. Other studies have found similar improved learning gains in courses that employ an active learning approach, and the researchers who have conducted these studies credit these gains to the nature of active engagement itself and not to any extra time spent studying the topic.

Why Cooperation and Collaboration Matter

All of us have experienced the dynamic, multiplying power of working in a healthy collaborative relationship. Cooperation is one of the most fundamental of human activities, the glue of our society, the engine of our deepest and most important relationships. Collaboration and cooperation can also be key drivers in successful active learning experiences, particularly in smaller courses. For more than 40 years, the brothers David and Roger Johnson (both long-time faculty members in the Education department and founding directors of the Cooperative Learning Institute at the University of Minnesota), have studied cooperative learning techniques in the classroom and collected empirical evidence about the impact of cooperation and collaboration on student learning. To learn more about cooperative learning and some popular approaches to its use in the college classroom, we'd recommend this introduction written by two chemical engineering professors from North Carolina State for a symposium on active learning in the analytical sciences.

How Cooperation & Collaboration Affect Learning

The Johnsons' findings are both convincing and compelling. In their book, Active Learning: Cooperation in the College Classroom, the Johnsons and their research collaborator Karl Smith reviewed nearly a century of research into cooperation and reported that cooperation improved learning outcomes in nearly every instance. In 1998, they published a short article in the journal Choice which summarized their views on cooperation and its impact individual student learning, and in 2009, they produced what was essentially a concise summary of their career work in Educational Researcher, both of which are well worth reading. They have described successful cooperative learning situations as possessing the following essential elements:

- Positive interdependence (each group member depends on and is accountable to others, providing a strong incentive to help and accept help from their peers)

- Individual accountability (each person in the group learns the material)

- Promotive interaction (group members help one another, share information, offer clarifying explanations)

- Social skills (group members must practice leadership, communication, compromise)

- Group processing (group members must regularly assess how well they are working together and make necessary adjustments)

The Johnsons and other researchers have found that when these elements are present in a cooperative learning setting, the gains in learning that students experience can be enormous. Cooperative learning doesn't only impact academic achievement, either; it has repeatedly been shown to improve the quality of learners' interpersonal interactions, their self-esteem, and their retention in schools or academic programs. As an added bonus, there is some evidence that collaboration is particularly effective for improving retention of traditionally underrepresented groups, which is a major point of concern at UW-Madison. For instance, one meta-analysis of the impact of small-group learning by Leonard Springer, Mary Elizabeth Stanne (educational consultants then based in Madison, and Minnesota, respectively) and Samuel Donovan (then a biology professor at Beloit College) found that small-group learning had a "significant and positive" effect on achievement, persistence, and attitudes among undergraduates, and that this positive impact was "significantly greater for groups composed primarily or exclusively of African American and Latinas/os compared with predominantly white and relatively heterogeneous groups." They also attempted to determine the impact of the amount of time students spent working together on student learning outcomes and attitudes. They found that medium group time had the highest correlation with achievement-related effects, but that high amounts of group time had the strongest positive impact on students' attitudes (to learn more about their criteria for group time or their specific findings, please refer to the study itself).

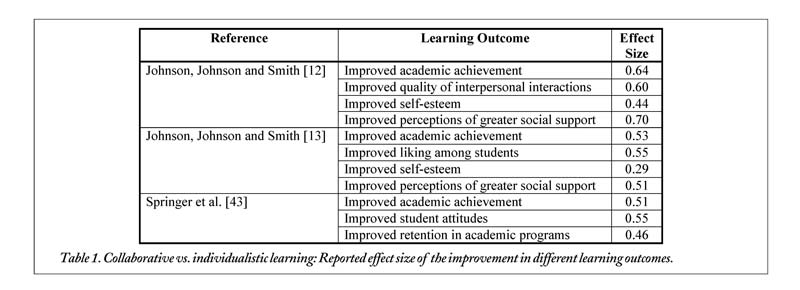

In a 2004 review of the evidence for active learning's impact, engineering professor Michael Prince summarized the major meta-analyses of cooperative learning then extant and presented the following tables of cooperative learning's effect size on various learning outcomes relative to individualistic or competitive approaches:

While effect size can be a difficult idea to grasp (especially if you're not a stat-head who already works with it as a measure), Prince explains that with respect to academic achievement, even the effect documented in the lowest of the three studies cited (Springer et al.) would move a student from the 50th to the 70th percentile on an exam, and would be roughly equivalent with raising a student’s grade from 75 to 81.

After surveying the available evidence, Prince (an engineering professor) concludes, "Looking at what seems to work, there are significant positive effect sizes associated with placing students in small groups and using cooperative learning structures," which I imagine is engineer-speak for "Holy cow, this active and cooperative learning stuff really seems to work!" If that's indeed what he is saying, we agree!

Additional Reading:

We made reference to a few different studies on the impact of involvement and collaboration/cooperation on learning on this page. While each of the studies are linked to above, we're collecting each of them here in one place for your convenience.

- Alexander Astin's "Student Involvement: A Developmental Theory for Higher Education" (originally published 1984).

- Richard Hake's "Interactive-engagement versus traditional methods; A six-thousand-student survey of mechanics test data for introductory physics courses" (1998). [Warning: the author is a physicist, and the article certainly reads that way. Not for the faint of heart.]

- Richard Felder and Rebecca Brent's "Cooperative Learning" (2007)

- David Johnson, Roger Johnson, and Karl Smith's "Cooperative Learning Returns to College" (1998).

- David and Roger Johnson's "An Educational Psychology Success Story: Social Interdependence Theory and Cooperative Learning" (2009).

- Leonard Springer, Mary Elizabeth Stanne, and Samuel Donovan's "Effects of Small-Group Learning on Undergraduates in Science, Mathematics, Engineering, and Technology: A Meta-Analysis" (1999).

- Michael Prince's "Does Active Learning Work? A Review of the Research" (2004).

What's Next?

In the next section we'll look at active learning spaces on campus (and beyond!), and in the third section we'll explore some specific practical ideas to increase student involvement and cooperative learning in the small- to mid-sized classes you teach or help support.

Active Learning Spaces

Observe & Consider

Observe & Consider

Active learning classrooms are teaching and learning environments designed with a more student-centered teaching approach in mind. These spaces often include modular furniture that can easily be rearranged and reassembled, moveable writing surfaces, and integrated technologies that support instructors' desires to increase their students involvement by integrating media, peer-to-peer interaction, and collaborative learning activities into their teaching. A key feature of active learning classrooms is their flexibility; the furniture and design choices allow for various room configurations, respond to natural traffic patterns and the "flow" of learning and teaching in that space, and accommodate diverse groupings of students. This design principle of flexibility creates a class environment that can transition easily between class components or activities, like an instructor's presentation, small group work, or student-led demonstrations. As you might imagine, these types of classrooms expand options for teaching and help support the many ways that different students learn.

In the following podcast, Steel Wagstaff from L&S Learning Support Services continues last week's conversation with Jim Brown, an assistant professor in English; Mary Claypool, a recent Ph.D. in the Department of French and Italian; and Beth Fahlberg, a clinical associate professor in the School of Nursing. This week, they offer advice for integrating active learning into smaller enrollment courses and talk about their experiences with active learning spaces:

Download the .mp3 (right-click and 'save link as')

Observe & Consider

Observe & Consider

Active learning classrooms are popping up all over our UW-Madison campus and in higher education environments, but these classrooms have long been a key element of primary education (think the square, four-person tables of a kindergarten classroom or moveable group work tables in a middle school lab setting). Scale-Up (Student-Centered Active Learning Environment for Undergraduate Programs) is a leading national organization that helps to support, define, and advocate for active learning spaces in higher education. Many of our peer universities are also highly engaged in active learning classroom design and implementation and have produced helpful resources encouraging others to build active learning classrooms on their campuses. The University of Minnesota and McGill University both have very well regarded active learning classroom initiatives and are actively publishing current research on best practices for active learning spaces and class environment design (for instance, see McGill's report on their 2009 active learning redesign).

The UW-Madison has been quite engaged in active learning classroom redesign, especially for new buildings and classroom remodeling projects. Take a look at some of the great initiatives on our very own campus!

The Wisconsin Collaboratory for Enhanced Learning (WisCEL)

WisCEL hosts some of the best-known active learning spaces on campus. Current WisCEL spaces are in operation in College Library and Wendt Commons in the School of Engineering (with more WisCEL spaces hopefully to be added in the future). WisCEL's goal is to provide collaboration-friendly and technology-enchanced learning spaces that increase student success and support and encourage innovative pedagogies and course design. Find out more about WisCEL by reading this brief descriptive fact sheet or by watching a short video demonstrating a WisCEL course in action:

College Library Media Studios

Just one floor below the WisCEL space in College Library are the Media Studios (connected to the DesignLab space). These bright and welcoming classrooms support courses that integrate digital, multimedia, or otherwise collaborative project-based assignments and design into the curriculum. These are the classrooms that Jim Brown describes using in this week's podcast. You can read more about the adjacent DesignLab and its connection to these spaces in this library news article from last year. If you're interested in teaching in one of these space, see the news item we posted last week. Make sure that you get your application in soon, as these spaces fill up quickly!

Classrooms in the new Nursing, Human Ecology, and Education buildings

The UW-Madison's School of Nursing has long been involved in active learning initiatives and is one of the main innovators of active learning space use on our campus. Their new building, Signe Skott Cooper Hall (currently under construction near the Health Sciences Learning Center), is based entirely on scalable and sustainable principles of active learning classroom design. Beth Fahlberg, who you can hear more from in this week and last week's podcast, has written a useful guide to what works best in an active learning space, based on the School of Nursing's experience with active learning classrooms.

Read more about the active learning spaces in the new Cooper Hall School of Nursing building:

The School of Human Ecology's new Nancy Nichols Hall (opened in 2012) and the renovated Education building (renovations completed in 2011) are not only a great example of active learning classroom design (as seen in the SoHE Learning Hall at right) but also of great space design in general! Each of these buildings incorporates myriad flexible learning and teaching spaces for collaborative work, presentations, studying, and small group projects.

Other flexible classroom spaces (like 290 Van Hise)

Many unique flexible classroom spaces exist on our campus, tucked away in various buildings and hallways. One example is our new videoconferencing and collaboration space in 290 Van Hise. This space, like other flexible learning spaces on campus, incorporates modular furniture, a movable teaching station and standing whiteboards, and integrated technology and media support to enhance teaching initiatives and active learning-based course design. Come down to 290 Van Hise to check out the space!

Many spaces you already teach in!

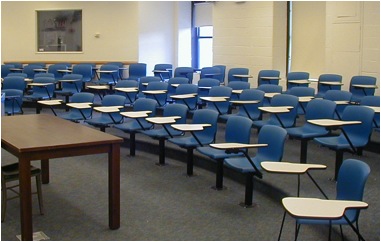

The rooms to the right likely look familiar to you as representatives of more traditional classroom spaces around campus. While many of the spaces we use on a daily basis weren't built with all of the affordances of active learning in mind, with a little bit of imagination, some elbow grease, and a willingness to reconceptualize your classroom environment, these too can become active learning spaces!

Even if you take simple steps such as moving a few classroom items around, reconfiguring the furniture, or redesigning parts of your course to allow for more group work (or muster up enough daring to occasionally take your class out of the classroom entirely and into a new and different "active learning" space, like Bascom Hill), you'll have moved toward modifying your traditional classroom into a space that more readily invites the kinds of active learning we've been discussing. In fact, that's just what we'll do in our Share & Connect activity...

Share & Connect

Share & Connect

Redesign a space for active learning

Now that we've discussed several considerations for active learning spaces, design, and environments, we'd like you to explore ways that you'd make a more traditional teaching space more friendly to active learning. This can be either very conceptual or wholly practical, depending on what's most helpful to you: you can completely redesign the space (ignoring any structural or pragmatic limitations) or just reorganize the room (moving furniture around, bringing furniture in, etc.) to accommodate an active learning activity. The sky's the limit!

Pick a space you teach in or have taught in OR use the sample small lecture room at right as your template. Identify some changes you'd make, and share them in the discussion space. Chime in with ideas and feedback for other class participants, too.

Practical Active Learning Ideas for Smaller Classes

Observe & Consider

Observe & Consider

"Learning To Draw": Active Learning from the Learner's Perspective

In last week's discussion, I [Steel] said that I wanted to learn how to draw during this coming year. Well, I was eating lunch with Bill Costello, one of Learning Support Services student workers, and he mentioned that as a fifth year senior he had a few extra spots for electives this year and had decided to take a drawing class. I got excited, and asked if he'd take some time to make a short film with me discussing active learning from an undergraduate learner's perspective and give me a short drawing lesson so I could get started on my own learning goal. He did, and thanks to David Macasaet, our resident filmmaker and media production guru, we made this short film, "Learning to Draw." Enjoy!

Observe & Consider

Observe & Consider

Last week, we devoted an entire section to Active Learning models and approaches, suggesting that many approaches to active learning could fit into 4 broad categories. This week, we wanted to provide specific instances from among these broad categories that have been successfully applied to small classes as a way of helping you to think about strategies that might work in the courses with which you are involved.

Ask Better Questions

Here are some ideas:

- Encourage divergent responses: To encourage dialogue, pose questions that might elicit differing opinions and allow multiple students to respond before weighing in or redirecting the conversation.

- Reverse the paradigm: Give students some responsibility in asking good questions by establishing a framework that guides student generated questions. Giving students input can help students take ownership in the class discussion.

- Follow up: Ask students to describe how they arrived at an answer.

- Get comfortable with silence: there's a broad base of research that shows that if you waiting briefly before calling on someone to answer, more students feel like they have time to think about a question, ensuring a higher quality of discussion.

- Consider Bloom's Taxomony: Align the question with the goal for your activity. Know whether your question seeks an answer that demonstrates knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, or evaluation.

Write and Reflect in Class

Planned writing and reflection activities, from low- to high-stakes, and from formal to informal, offer a great way of increasing student engagement and triggering meaningful learning. We'll look more at writing as active learning in week 4, but for now here are a few ideas for implementing writing and reflection in smaller classes:

- Assign a rhetorical model: Ask students to follow a pattern or a template for a written assignment (compare and contrast, definition, film or book review, analysis, exemplification, etc.), provide opportunities for peer review or other revision, and provide them feedback.

- Three-Minute Papers: At the end of a class session, invite students write for three minutes in response to a specific question (it could be as open-ended as "What's the most important thing you learned today?" or "Which concept or idea from today's class was the most difficult for you to understand?" or "What was the most confusing part of today's class?").

- Concept Evaluation: Make a handout with several likely student questions on your topic for that day and ask students to circle the ones they don't yet know the answers to and turn in the paper. A variation of this activity could be to distribute a 3x5 card to each student with a statement related to content knowledge written on it. Half should feature true statements, and half should make false claims. Students must decide if their card's statement is true or false, using any available means and must group themselves on one side of the room or the other. After grouping, the whole class works through the claims, discussing their accuracy and reviewing the ideas on each card.

- Letter of Advice: Near the end of a course ask student to write a letter of advice to future students on how best to succeed in your course.

- Conceptual Haiku: After students have been introduced to a new topic or concept, ask each of them to write a haiku (a three-line poem which follows a simple syllabic pattern, 5 syllables, 7 syllables, 5 syllables) on that topic and share their writing with a classmate or small group.

- Directed Paraphrasing: Ask students to paraphrase part of a lesson for a specific audience and a specific purpose (when possible, try to make this activity useful by giving it a real-world connection).

- Word Journal: In a similar assignment, ask students first to summarize an entire topic with a single word. Then give them 5 minutes to produce a paragraph which explains their word choice

- Focused Reflection: After an in-class experience/activity, ask students to reflect on “what” they learned, “so what” (why is it important and what are the implications), and “now what” (how to apply it or do things differently)

Solve Problems

Posing meaningful problems with a direct connection to your academic discipline, course content, or subject area and inviting students to develop creative solutions is a fantastic way to catalyze meaningful learning. Here are some ideas:

- Case studies: Immerse students in an authentic context using case studies that illustrate how course concepts map to the real world. See more about how the UW Engage program is helping instructors develop interactive case scenarios.

- Decision making model: Present a problem and have students use John Dewey’s decision making model in groups. This model follows this basic structure: (1) Diagnose several possible causes, (2) search for alternate solutions, and (3) evaluate alternatives to choose the best solution.

If you're planning to introduce problem-solving activities to your class, consider these means-tested approaches and advice adapted from AJ Romiszowski's "The development of physical skills: instruction in the psychomotor domain." in Instructional-Design Theories and Models: a New Paradigm of Instructional Theory, Volume 2 (1999).

- Model the problem-solving process for students.

- Let the student observe a sequential action pattern before attempting to do it.

- Demonstrate a task from the viewpoint of the performer.

- Setting specific goals can lead to more rapid mastery of a skilled activity.

- Involve students in producing a shared definition of what constitutes success.

- Ensure that students have a clear understanding of what it means to solve different kinds of problems.

- In general, ‘learning feedback’ (results information) promotes learning, and ‘action feedback’ (control information) does not.

- Letting students complete the problem-solving task before receiving feedback about their success promotes learning better than offering comments at each step in the solution.

- In general, feedback is more effective in promoting learning when it transmits more complete information. Students learning to solve problems need more than a simple assessment of whether their answer was correct or not.

- Transfer and retention of skills and abilities are improved by what educational researchers call 'overlearning.'

- The more problems students solve (with appropriate feedback), the more readily they will be able to solve novel problems, a defining characteristic of meaningful learning.

- Avoid too fast a progression to more difficult tasks. Present students with a sequence of problems that moves from easy to hard as their performance improves.

Collaborate and Cooperate

Successful collaborative or cooperative learning activities generally accomplish two things: they enhance student learning and autonomy and they develop social skills like decision making, role development, conflict management, and effective communication. Research into effective collaborative learning in the college classroom has found that there are three simple, often-overlooked components which enormously improve the quality of small-group work:

- Students should receive clear, explicit instructions about the tasks they are expected to perform

- An appropriate amount of time must be allotted for the activity and agreed upon in advance

- Students in the groups should agree upon their roles within the group. In most cases one student from the group should be assigned as a recorder/reporter and be charged with providing feedback when the group reports back to the larger class.

Here are some ideas for cooperative activities:

- Peer teaching: Form a group assingment that requires students to lead a class (or portion of a class). Require more than just a presentation.

- Role play: Organize a discussion where students assume the role of characters in a hypothetical situation. Shedding their real identity provides learners freedom to disagree and consider alternate perspectives.

- Scenarios: Build activities around realistic scenarios (perhaps current events) to give an opportunity to apply abstract concepts.

- Create healthy competition: Develop competitive exercises (games) that allow learners to challenge and motivate one another (Game-based learning).

Practice & Apply

Practice & Apply

Let's put some of these ideas into practice. Use either your own course or one of the two mock course scenarios below as a template. Picture how a typical class day in this course might go: What are the activities? How is the hour structured? How is a lecture delivered? Are the students engaged with the material, and if so, how exactly? Now choose a short segement of this class (10 to 15 minutes) and reimagine that segement as a short active learning mini-module. Use our session notes, discussions, and ideas above to help guide you and to help you construct your active learning mini-module. Remember, active learning can be applied to your course design slowly and in small chunks; it does not have to be as dauting as sitting down to redesign your entire semester-long course all at once! Let this activity encourage and inspire you, and perhaps you might even incorporate the mini-module that you reinvent here into your course sometime soon!

Sample Scenarios:

- A mid-sized History lecture course (about 50 students). The course is mostly lecture-based, and while the students seem interested in the material, they aren't quite as engaged as they could be. It is still early in the semester, so some community-building activities couldn't hurt to help to encourage a more cohesive group. The course meets twice per week for 75 minutes each time. The course is currently only face-to-face with no online or blended course components.

- A small, intensive, upper-level literature course (about 18 students). The students are very familiar with the course materials but don't seem to grasp entirely the current analytical approach that you're discussing in class. The course meets four times per week for 50 minutes. The course does include some blended and online elements for out-of-class practice and a few assignments.

Closing & Checklist

End of Week 2

Thanks for completing Week 2 with us! In this week of our Active Learning online workshop session, we

- Identified the evidence for active learning's effectiveness at improving learning outcomes in smaller courses

- Explored some of active learning spaces around campus and analyzed the way that teaching space can be adapted for active learning goals.

- Selected, created, and modified activities or assignments to increase their active learning potential in a small class environment.

Upcoming in Week 3

In Week 3 of this session, we will:

- Identify relevant pedagogical approaches, models, and environments for large lecture courses and labs.

- Discuss strategies for teaching in large active learning courses and for helping your students navigate this model of instruction

- Demonstrate our ability to create, improve, or modify existing activies or assignments to increase their active learning potential in a large lecture class environment.