L&S

Learning

Support

Services

presents

TEACHING with TECHNOLOGY

ONLINE WORKSHOP SERIES | 2012-2013

Welcome to Active Learning

Active Learning?

Yeah, you heard right. ACTIVE learning. The phrase may conjure up all kinds of images and associations, from shop class to Montessori preschools to new age creative writing instructors who lead participatory vision quests and don't believe in grades, structure, or lecturing, to imaginative peers who struggled in the disciplinary regimes of old-school instruction, like our good friend Calvin:

While we'll introduce and explore a few approaches to active learning together as the week continues, we wanted to provide a few initial assumptions up front to help introduce you to the topic as we understand it. In its most elemental form, active learning means doing things and thinking about the things that you're doing (what psychologists call metacognition).

Countless examples from the history of education demonstrate both that people tend to support what they help create and that meaningful learning is strongly correlated with learners’ active involvement in learning processes. All of us want to be better learners and to stimulate meaningful learning for others, and there’s a (growing) mountain of evidence that when properly applied, active learning can help in major ways: it’s challenging, it’s effective, it’s participatory, and best of all, it’s fun!

This online workshop session on active learning is intended to instigate meaningful learning and thoughtful reflection about your own participation in teaching and learning. Wha? A module on active learning that itself employs active learning techniques? Meta-cognition about meta-cognition?

Yep. In this session we'll provide some means-tested, effective ways to incorporate active learning into your lives, introduce you to some of the ongoing conversations around the topic in higher education, and invite you to take an active role in constructing useful knowledges on this topic. Let's get started!

Share & Connect

Share & Connect

One of our favorite Google search capabilities is the [define: TERM] operator. You can use this by entering the word ‘define’ followed by a colon and the term or phrase you’re interested in exploring in greater depth into the Google search bar. The search screen will show a response to your query that offers a brief definition, selected by Google’s algorithms, that it believes best defines your word or term. Clicking on the ‘more info’ link on the results page will take you to several other contextual definitions for your word or phrase. Here’s what it looks like for the term ‘syzygy’:

Activity: Active Learning Definitions

- Try the [define:*] query for the phrase ‘active learning’. Click on "More info" (shown above) and review the search results.

- Post the definition that seems most compelling to you (along with the source) under the "Compelling definitions from the web" heading on our Active Learning Definitions Wiki Page.

- Now develop your optimal definition of active learning. Consider your own teaching and learning style and your educational philosophy. Post your definition under the "Your optimal definitions" heading on our Active Learning Definitions Wiki Page.

- Read and consider definitions from your peers!

Introduction to Active Learning

Observe & Consider

Observe & Consider

Week 1 Objectives

- Define active learning

- Survey various models of active learning

- Understand why active learning is pedagogically effective

- Identify opportunities and benefits to using active learning

- Begin to implement feasible pedagogical approaches to active learning

Active Learning: A Working Definition

Now that you’ve read some of the definitions of ‘active learning’ floating around on the free web and created your own working definition of the term, we’d like to share some of our ideas about active learning, offer some history and context for the term, and explain why we believe it can help you accomplish many of your own personal learning (and teaching) outcomes.

Earlier we wrote that active learning could be simply defined as doing things and thinking about what you're doing. While that's true, another functional definition of active learning would be the intentional construction of skills, abilities, or knowledges through participation or contribution. We believe that active learning does the following:

- requires high levels of involvement in information gathering, analyzing, and problem solving processes

- invites reflection upon ideas and how one has, is, or will use those ideas, and

- includes regular assessments of one’s degree of understanding and skill at handling concepts or problems in a particular discipline.

Active learning, in our experience, is also closely allied with what many educators refer to as Student-Centered Instruction [SCI]. Student-Centered Instruction is an approach to instruction which prioritizes the abilities, needs, and interests of the student (learner), so that student needs determine course content, activities, materials, and pace of learning. Instructors provide structured opportunities for students to learn independently and from their peers, encouraging them to become fully involved in their own learning and coaching them as they develop any skills they need to do so effectively.

Here are some general characteristics of active learning:

- Learners do more than just listen.

- Learners engage in structured, exploratory activities that stretch their current levels of knowledge and ability.

- Learners construct knowledge together, working collaboratively, exchanging ideas, testing, extending, developing, and evaluating each others' ideas, and sharing instructional responsibilities.

- Learners devote significant amounts of physical, psychological, and intellectual energy to learning tasks and class projects.

- Learner effort is focused more on acquiring and developing skills and competencies than on receiving transmitted information or explanations.

- Learners are involved in higher-order thinking and making activities (analyzing, synthesizing, evaluating, creating, translating).

- Learners regularly monitor and evaluate their own attitudes and values.

While we believe that all participants have a shared responsibility for producing an environment conducive to active learning, it's true that instructors still bear much of the responsibility for cultivating spaces where active learning is the norm and learners can flourish in the ways described above. In the next pages of this module, we'll explore some of the ways that instructors have helped facilitate active learning, but first, we want to invite all of you to think about and share some of your own succesful experiences as active learners in the activity below.

Share & Connect

Share & Connect

Discussion Activity

In this activity, we'd like to use the class discussion forum as a way of getting to know other class participants a little better as well as sharing learning goals, ideas, and tips. Please answer the following questions:

- What's something that you made a conscious effort to learn in the past year?

- What were some of the methods you used to learn this thing? Which of these methods did you find most useful to you in your learning process?

- What's something you'd like to learn in the coming year (feel free to borrow ideas from others in the class!)?

- Read your peers' responses. Based on your own prior experiences and the experiences described by fellow class participants, what are some learning methods that you will certainly pursue in accomplishing this goal?

History & Context for Active Learning

Observe & Consider

Observe & Consider

The idea that meaningful learning requires active engagement is an ancient one, and while it is not especially revolutionary, our contemporary educational practices don't always reflect what we believe or know about active learning. On this page, we'll take a look at some of the thinkers and ideas which have been most influential on our current ideas about active learning and effective student-centered instruction.

Active Learning and 'Constructivism'

The term "active learning" and the related idea of "student-centered" (rather than "teacher-centered") learning became prominent nodes of interest among educators during the late 1970s and early 1980s. As their era's leading buzzwords, they filled much the same role that blended learning and MOOCs are filling today. Over the past few decades, an increasing number of teachers, educational researchers, cognitive psychologists, and instructional designers have shown sustained interest in developing, propagating, and evaluating models of teaching and learning that afford greater opportunities for participation, exploration, and collaboration to students and learners.

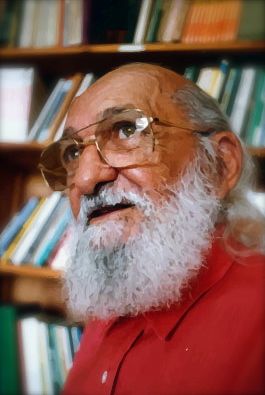

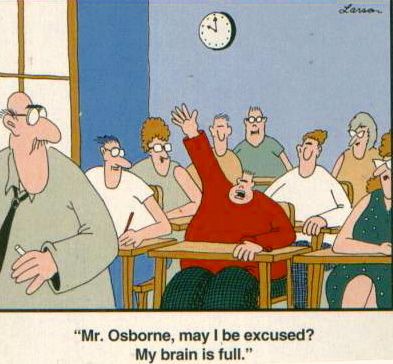

One of the most important contributions that proponents of active learning have made to our idea of effective education has been its revision of the defining metaphors we use to imagine teacher/student interaction. For some educational reformers, like Paulo Freire, prominent teaching methods of their day seemed to be founded on what they described as a "banking model." In this model, teachers behaved as if information could be directly transmitted from subject experts to novice learners, who passively received and deposited their lesson's content, filing it away or memorizing it for later withdrawal. Some even visualized education as the filling of smaller, mostly empty vessels [students] with content knowledge poured out from a large, overflowing vessel [instructor], an idea that's satirized deliciously in the Far Side cartoon below:.

In the place of these metaphors of teaching and learning, proponents of active learning have stressed that learning is an active process, and have developed metaphors of teaching and learning rooted in a “constructivist” philosophy, which posits that knowledge is never merely transmitted between individuals, but is a dynamic capacity constructed by the learner using internal thought processes and acting on environmental stimuli. In other words, learning involves the active construction of meaning by the learner, who combines new information with existing mental models in order to make sense of the world that they encounter. Instead of receiving and importing ready-made knowledge, learners build mental representations or models of the “real world” that they use to solve problems. These representations can be well or poorly formed but are continually accessed and updated by each individual learner, including the individual(s) responsible for filling the traditional role of the instructor. In the sections below, we'll look at five thinkers whose ideas have provided many of the underpinnings of modern constructivist ideas of learning.

John Dewey

In American education, one of the earliest and most influential advocates for what we would now call ‘active learning’ was the philosopher and educator John Dewey [1859-1952]. In his influential book Democracy and Education [1916], Dewey wrote that learning means something which the individual does when he studies. It is an active, personally conducted affair.

Dewey believed that people come to understand themselves and the world through their interactions with other people and things in the world, and that the purpose of education is to produce an environment in which useful interactions could be developed and sustained. He emphasized the need for active learning when he claimed that there is no such thing as genuine knowledge and fruitful understanding except as the offspring of doing. The analysis and rearrangement of facts which is indispensable to the growth of knowledge … cannot be attained purely mentally—just inside the head. Men have to do something to the things when they wish to find out something.

To learn more about Dewey’s ideas, we recommend reading "My Pedagogic Creed" [1896], which succinctly presents many of his ideas about the purpose of education, or his book Democracy and Education [1916].

In the following video, A.G. Rud, Dean of Washington State University’s College of Education, describes Dewey’s lasting impact on education:

Maria Montessori

The Italian doctor and educator Maria Montessori [1870-1952] developed an educational philosophy in the early part of the 20th century that has had a massive impact on the way that chidren and young adults around the globe experience learning. In a series of influential books she published between 1909 and 1917, Montessori laid out what she called a "scientific pedagogy" that emphasized mixed-age classrooms, student autonomy, uninterrupted opportunities for creative exploration, and carefully designed learning environments. Over the subsequent years, her educational ideas gained traction across several continents, so that today that are an estimated 30,000 schoold currently using some version of Montessori education. In her book, Education for a New World [1946], Montessori provides a good summary of her basic ideas regarding the ideal student-teacher interaction by declaring that Education is a natural process spontaneously carried out by the human individual, and is acquired not by listening to words but by experiences upon the environment. The task of the teacher becomes that of preparing a series of motives of cultural activity, spread over a specially prepared environment, and then refraining from obtrusive interference.

If you'd like to read about Montessori's approach to pedagogy in her own words, we recommend her book The Montessori Method [1912].

Gilbert Ryle and the Distinction Between Knowing How and Knowing That:

In 1945, the British philosopher Gilbert Ryle [1900-1976] published an influential lecture in which he argued that philosophers had not paid enough attention to the common-sense difference between two kinds of knowledge: knowing that something is the case and knowing how to do things, a distinction which has come to be known as the difference between declarative and procedural knowledge (knowing that and knowing how, respectively). In Ryle’s lecture, he observes that I can't be said to have knowledge of [a] fact unless I can intelligently exploit it. … Effective possession of a piece of knowledge-that involves knowing how to use that knowledge, when required, for the solution of other theoretical or practical problems. There is a distinction between the museum-possession and the workshop-possession of knowledge.

Ryle's ideas, developed at greater length in his subsequent work, especially The Concept of Mind [1949], have been of special importance for psychologists and educators interested in developing active learning processes which facilitate meaningful learning by increasing procedural rather than declarative knowledge.

Jean Piaget

The Swiss psychologist and educational philosopher Jean Piaget [1896-1980] is best known for his study of children's cognitive development, and his interest in how learner's construct knowledge. For Piaget, knowledge was the ability to modify, transform, and operate on an object or idea in a way that grants the learner understanding through the process of use or transformation. He believed that learning was an activity, and that in emerged from experiences the learner had, both physically and logically, with objects around them. In a late-career interview with Jean-Claude Bringuier, Piaget stated that Education, for most people, means trying to lead the child to resemble the typical adult of his society ... but for me ... education means making creators ... You have to make inventors, innovators—not conformists.

Piaget's ideas have had an enormous influence on our contemporary understanding of childhood development and our ideals of teaching and learning. To understand more about Piaget's thought, we'd recommend looking at The Moral Judgment of the Child [1932], one of his most significant books.

You can watch Piaget explain his constructivist position, with examples from experiments conducted with young learners below:

Lev Vygotsky and the Zone of Proximal Development

Another developmental psychologist whose ideas have been particularly important to contemporary ideas about active learning was Lev Vygotsky [1896-1934]. While Vygotsky produced several works of great importance, his most influential idea is probably his conception of the Zone of Proximal Development [ZPD]. The zone of proximal development is the distance between what an individual learner is currently able to do independently and what they have shown an ability to do under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers. Vygotsky believed that what children are able to do with the assistance of others is even more indicative of their present level of mental development than what they can do alone. The zone of proximal development offers a way of thinking about what kinds of things an individual is best prepared to learn and master for themselves, and helps teachers and learners identify knowledges, skills, or abilities that are currently at the upper level of a learner's competence. In other words, the zone of proximal development focuses not on what I can already do, but what I am almost able to do. For most learners, their zone of proximal development is always changing, since the things that they can perform today with assistance they will soon be able to perform independently, growth which prepares them for further learning. This idea has great relevance for models of active learning, since they often emphasize the value of collaborative exploration and peer teaching and focus on the the practical acquisition of procedural knowledge.

Share & Connect

Share & Connect

If you've made it this far, congratulations! In many ways this page focused on declarative knowledge and employed a lot of the techniques and approaches associated with older, more passive forms of instruction that we disparaged as being part of the "banking" model in the opening paragraphs. So here's something for you to do if you'd like to make this a more active, participatory experience:

Step 1: Reflection

Think back to the most significant educational experiences you've had. As a learner, who has been particularly influential in your life? It could be a parent, a grade-school teacher, a college professor, a roommate, a fellow member of a bookclub, a river rafting guide, anyone whose teaching style made a difference for you, who initiated meaningful learning. Do you have someone in mind, someone who helped or inspired you to become an active learner? Good.

Step 2: The Gratitude Project

Make a plan to communicate to this person how their influence on your learning has benefited you. Tell them, sincerely, how they made a difference in your life and thank them for what they've done. There are many ways to do this: write a letter (anonymous or signed), send an email, make a phone call, visit face to face. You choose the means of communication, but the challenge is the same for everyone: to express gratitude to this guide or teacher.

Step 3: Trace a Genealogy of Influence

The next step in this challenge involves becoming an active learner again. As a part of your exchange with this influential guide or teacher, ask them who or what influenced their teaching style, approach to learning, or educational philosophy. Find out how they become the guide or teacher that they became, who or what influenced their growth and learning, and share your own experiences and insights where relevant. In our experience, this conversation can be just as rewarding as Step 2, and sometimes even more illuminating.

For example, when I [Steel] was doing this activity for myself, I chose my mother, and was surprised to hear her tell me about how she had started and run something called a "joy school" for me and several neighborhood children when I was very young. Without my even knowing it, Richard and Linda Eyre, the founders of the joy school movement, had been indirect influences on my own early learning experiences, and I've made it a goal to learn more about this program, its founders, and its educational philosophy during the coming weeks.

Step 4: Repeat and Revise

We've tried to show on this page how many of the best ideas and practices of the contemporary higher education have their roots in the experiments and convictions of teachers from the past. We believe that this is true for almost any idea or practice, that nearly everything we believe, know, and do has a rich and interesting contextual history, a past worthy of exploring. As you investigate the roots and influences of the experiences and knowledges that are most meaningful in your own life, you'll find unexpected things that you'll want to learn more about. When it comes to investigating the impact and influence of meaningful teachers, the potential for infinite regress is immense (it seems to be a case where it really is turtles all the way down!) We hope that you'll continue broadening and deepening your exploration and that you'll share the fruits of your inquiry by encouraging others to branch out, dig deeper, and connect more widely as they take responsibility for their own active, meaningful learning.

Active Learning Models & Approaches

Observe & Consider

Observe & Consider

In the following podcast, Steel Wagstaff from L&S Learning Support Services facilitates a conversation about active learning approaches with Jim Brown, an assistant professor in English; Mary Claypool, a recent Ph.D. in the Department of French and Italian; and Beth Fahlberg, a clinical associate professor in the School of Nursing:

Download the .mp3 (right-click and 'save link as')

Observe & Consider

Observe & Consider

Models of Active Learning

Active learning can take many forms, follow different models, and serve many different instructional goals. Many of these approaches have areas of overlap with each other and draw on similar pedagogies that focus on student-centered instruction and course learning objectives. In this way, active learning module and lesson design planning relies heavily on the >backward design process (discussed at greater length in Week 2 of our Blended Learning Module, where instructors will identify and craft key learning objectives for their students and then work "backward" to design assessment opportunities and in- and out-of-class activities that respond to these learning objectives and help the students be successful in achieving them. This helpful Educause article on active learning design by 3 Virginia Tech educators briefly touches on a few of these key design elements and how some might be unique to the active learning environment.

We'll explore these approaches in greater detail and look at some concrete examples of active learning ideas for both smaller courses and large-lecture sections in Weeks 2 & 3, but here are a few active learning models and pedagogical approaches to get us started:

Collaborative Work

Collaborative active learning emphasizes structured group work, sharing, and project coordination in order to solve an academic task or to learn or develop a new skill. This group work can take the form of pair work, small groups of students, or all-class collaboration. Many of these approaches draw on the use of partnerships and targeted working groups in the classroom environment and leverage the community-building energies that these groups foster. The effect can be increased student engagement, student accountability for their participation and group contributions, and enhanced class cooperation.

Examples of collaborative work activities include:

- Peer tutoring

- Class debates

- "Share out" and interactive discussions

- Group projects

- Student- or group-led lessons (or portions of a lesson)

Some teaching approaches that can work well with collaborative work activites are: inquiry-based teaching, peer feedback or evaluation strategies, independent (or student-led) project assignments, and student-driven pedagogies. A few great examples of UW-Madison collaborative work environments or resources that model collaborative work are the DesignLab (in College Library), The Writing Center, and GUTS peer tutoring.

Problem- & Inquiry-based Learning

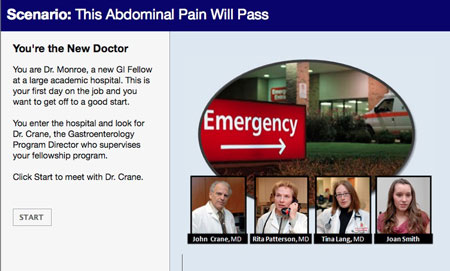

Problem - and inquiry-based learning activities have a flexible format but typically follow a pattern of diagnosis and evaluation of a challenge or problem. The students would be asked to 1) define or identify the problem or challenge, 2) diagnose potential reasons for this problem, 2) brainstorm and evaluate alternative solutions or options, and 4) choose the most appropriate solution and justify the reason for their choice. Problem- and inquiry-based learning asks the students to assume responsibility and a higher level of engagement with their learning process (and the teaching process) while also encouraging critical assessment, inquiry, and skillful analysis of course materials and topic content. These types of activities can often be very interactive and deeply rewarding for the students, since they frequently feel a sense of accomplishment while completing and sharing their findings.

Some examples of problem- and inquiry-based activities are:

- Case study analyses

- Independent projects

- Mock trials

- Strategic writing reflections

Some teaching approaches that can work well with problem- and inquiry-based learning activities are: discovery or self-exploration activities or processes, technology-enhanced role simulations, case-centered instruction, and model scenario training. Disciplines like physics, economics, nursing & medicine, and sociology often rely on problem-based learning strategies (as well as many other disciplines). One great UW resource for crafting problem- and inquiry-based learning activities is the Case Scenario Builder/Critical Reader tool created by DoIT Academic Technology.

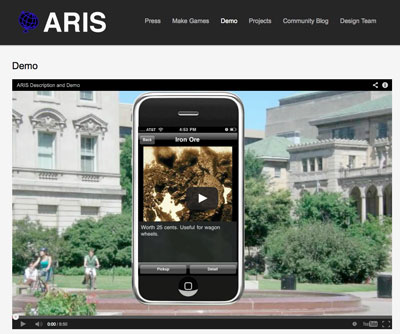

Games & Simulation Activites

Games and simulation exercises immerse students in responsive active learning environments that frequently simulate a real-life experience. These activities can help create learning situations that would not otherwise be available in the traditional classroom and allow safe, fun opportunities for learners to develop, practice, and improve coping skills for potentially stressful, unfamiliar, complex, or controversial situations. In addition to helping augment course materials, these types of activities can encourage personal initiative and often generate very high levels of motivation, engagement, and enthusiasm.

Some examples of games and simulation activities are:

- Technology-enhanced role playing (avatars, for example)

- Place-based gaming

- Game or puzzle creation

- Digital storytelling media

Some teaching approaches that work well with games and simulation activities are: problem-based learning (see above section for some additional details), technology-enhanced instruction, "third place" classroom teaching concepts (the idea that instruction can happen in a third space that is situated in or approximates the real world and is neither in the classroom or online). In addition to technology-enchanced gaming, other examples of games and situated learning activities can run the gamut from in-class mini dramas or play acting to study abroad scenarios. A few UW-Madison examples of game and situational learning resources include DoIT's ARIS program, WisCER's Epistemic Games Group, and Games+Learning+Society.

Read an article about epistemic games and their potential to help enhance student learning from the Epistemic Game Group in the Wisconsin Center for Education Research (WCER): "Assessing Learning in the 21st Century"

Space & Format Interventions

This model of active learning is a broader catchall term that refer to both changes in the physical environment in a learning space as well as adjustments of content and delivery to accomodate more active learning. Space and teaching format interventions can involve reorganizing and reconceptualizing the classroom space so that the environment better encourages independent student work, allows for a fluid and flexible use of class time and work, and fosters collaboration amongst students. This reorganization can range from rearranging class furniture and making other design modifications to establishing new teaching and learning "movements" which alter the classroom's 'traffic flow' to simply recognizing the different ways that people might naturally occupy a space when they're actively engaged in the learning process.

Some examples of space and format interventions are:

- Lab-type classrooms

- Enhanced or Interactive Lectures

- Emporium or collaboration areas

- Studio space

- Moveable furniture classrooms

Most any active learning teaching approach (or traditional teaching approach, for that matter) can work well in an active learning space. We have a growing number of these active learning spaces at UW-Madison, including the Wisconsin Collaboratory for Enhanced Learning [WisCEL] spaces in College Library and Wendt Commons.

If you'd like to learn more about these active learning spaces, check out "Learning in libraries: New center marries instructional and study space," a recent news article about the WisCEL space in Wendt Commons.

Observe & Consider

Observe & Consider

If you'd like to read more about active learning and explore details of some of the models and approaches mentioned above, here are some additional resources that we'd recommend. Again, we'll be discussing aspects of these models and approaches in depth in Weeks 2-3 when we address specific active learning goals, pedagogies, and activies in small classrooms, active learning spaces, and large lecture courses.

- A brief summary digest of Charles Bonwell and James Eison seminal 1991 book, Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom.

- Key ideas from Joel Michael and Harold Modell's Active Learning in Secondary and College Science Classrooms: A Working Model for Helping the Learner To Learn.

- We can't recommend the outstanding National Resource Council publication How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience and School highly enough. You can download the full-text of the book or check out these specially recommended chapters: on learning generally [Chapter 1], on designing active learning spaces [Chapter 6], and on teaching with technology [Chapter 9].

Guided Self-Assessment

Practice & Apply

Practice & Apply

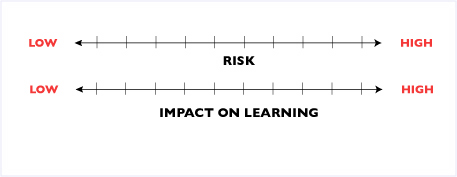

As we've seen in the previous section, there are a number of approaches to making learning more active. In this activity, you'll think though the implications of how a part of your course might work when using one or more of the four models of active learning. Keep in mind that high impact, low risk adaptations are ideal.

Instructions:

Download the Worksheet

Active Learning Guided Self-Assessment Worksheet To get started, download the Guided Self-Assessment worksheet to record your information, or use your own system to write down your notes.

Recall the Four Models of Active Learning.

Refer to the previous page for examples of how to align active learning with learning objectives. For quick reference, the four models for active learning are:

- Collaborative Work

- Problem- & Inquiry-based Learning

- Games and Simulation Activities

- Space and Format Interventions

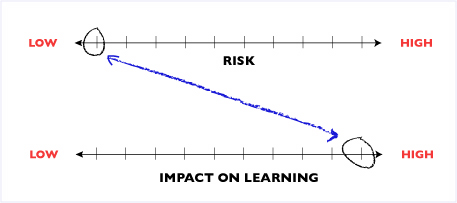

Assess the Risk and Impact of Adaptation or Redesign

Take note of where your changes fall on the spectrum of risk of implementation and impact on learning.

Risk of Implementation and Impact on Learning Spectrum

The ideal interventions combine low risk and high impact on learning -

Next Steps & Discoveries

What did you learn from this activity? What did you find out about the alignment of your ideas with their potential impact?

Week 1 Closing

End of Week 1

Thanks for completing Week 1 with us! In this week of our Active Learning online workshop session, we

- Defined active learning

- Surveyed various models of active learning

- Identified opportunities and benefits to using active learning

- Started to consider feasible pedagogical approaches for active learning

Upcoming for Week 2

In Week 2 of this session, we will:

- Identify relevant pedagogical approaches, models, and environments for small active learning courses

- Discuss strategies for teaching in small active learning courses and for helping your students navigate this model of instruction

- Analyze learning spaces and their utility for active learning

- Demonstrate your ability to improve existing activies or assignments to increase their active learning potential for a small class environment.